Phlebotomy-Related Injuries:

Is Your Next Patient at Risk?

Each year, specimen collection personnel who deviate from the standard for the procedure injure hundreds if not thousands of patients. Do you know the standard to which you will be held accountable? Do your coworkers? Does your staff or trainees? Could your procedure manual stand up to scrutiny should a patient be injured and seek compensation? The answers to these and other questions will determine your vulnerability to a phlebotomy-related lawsuit.

Each year, specimen collection personnel who deviate from the standard for the procedure injure hundreds if not thousands of patients. Do you know the standard to which you will be held accountable? Do your coworkers? Does your staff or trainees? Could your procedure manual stand up to scrutiny should a patient be injured and seek compensation? The answers to these and other questions will determine your vulnerability to a phlebotomy-related lawsuit.

To assess your potential to inflict injury on a patient during phlebotomy---and that of those you manage or teach, size-up the expertise where you work or teach against this top-ten list.

10. Reinvent the procedure

When an established procedure is tinkered with, things go wrong. Over the years, myriad homespun innovations have attempted to modify a standard that was first introduced in 1980. Crazy? You bet. If you're wondering "who would do such a thing?", so are we. It is imperative that all laboratory procedure manuals reflect the prevailing standard of care as established in the literature and CLSI standards and guidelines, and that any attempt to modify the procedure is disciplined. Failure to enforce the standardized procedure for venipunctures can be seen by a jury as falling beneath the standard of care.

9. Draw from unorthodox sites

Not all veins are fair game. The acceptable sites include the veins of the antecubital area, the back of the hand and the foot and ankle (only with physician's permission). Period. According to the CLSI standards, veins to the front of the wrist (palm side) or lateral wrists (thumb side) must not be used for venipuncture due the presence of nerves and tendons close to the surface. Drawing from veins in sites other than these may subject patients to injury to nerves, arteries, tendon and bone. Regardless of the site of the venipuncture, whenever one is about to insert a needle into a patient's flesh, one must have a thorough knowledge of the anatomy of that area in order to adequately assess the risk.

8. Seat the patient anywhere

Gravity happens. If it happens to your patient who has just passed out, the consequences can translate into injury and liability if you didn't position him properly. According to the standards, patients must be recumbent or seated in a chair with arm rests for support in case the patient loses consciousness. This means chairs without arm rests are not acceptable for venipuncture; nor are exam tables and patient beds unless the patient is recumbent. The standards also require patients with a history of fainting during blood collection procedures to be recumbent. Make sure your procedure manuals include these restriction and you are less likely to be subjected to the pain and anxiety that can come from being liable for injuries that result from improper positioning.

7. Turn your back on the patient

Statistics tell us that up to five percent of patients will pass out during or immediately following a venipuncture. Don't allow yourself to turn your back on patients before releasing them from their care. Pallor, perspiration, hyperventilation, and anxiety may be clues that the patient is going down. Being inattentive by turning your back to the patient or leaving the immediate area prematurely is not consistent with the required vigilance, and is one of the most common ways healthcare professionals who draw blood and their employers can be held responsible for injuries sustained during a venipuncture procedure.

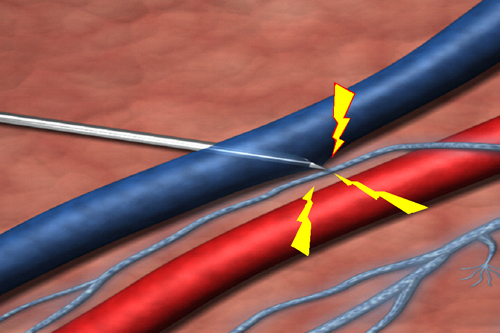

6. Draw from an artery

Not only is arterial blood and venous blood different in terms of the concentration of some analytes, but drawing from an artery is riskier to the patient. Besides the risk of nerve injury, arterial punctures are slower to seal and much more likely to lead to massive hematoma formation if adequate pressure is not applied. Therefore, post-puncture care requires far more caution, attention, and time when an artery has been pierced. According to the standards, arterial punctures must not be considered as an alternative to venipuncture in difficult draws. It increases the risk of complications, and litigation, significantly.

5. Bandage in a hurry

A bandage is not a substitute for pressure. The standards insist that we don't bandage a patient unless we are assured stasis is complete. That means we need to slow down, remove the gauze, and perform a two-point check for bleeding. The first observation is for superficial bleeding from the skin; the second is for hematoma formation. A quick peek under the gauze for superficial bleeding is never sufficient. Instead, observe the site for five to ten seconds to see what happens. Look for the raising or mounding of flesh, which indicates the vein is leaking into the tissue. Hematomas exert pressure on the nerves in the area. Such "compression nerve injuries" often lead to Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, which can be permanently disabling.

4. Disregard shooting pain

The "reasonable and prudent phlebotomist" (legalese for one who applies the standards every time she draws blood) knows that shooting, electric-like pain indicates a nerve has been provoked, and will remove the needle immediately. Those who disregard the patient in excruciating pain risk making a minor injury severe, and a temporary injury permanently disabling. If you are performing within the standard of care, you're removing the needle whenever the patient expresses unusual or extreme pain, tingling or numbness in the fingers or hand, and any electrical, shooting-pain sensation.

4. Disregard shooting pain

The "reasonable and prudent phlebotomist" (legalese for one who applies the standards every time she draws blood) knows that shooting, electric-like pain indicates a nerve has been provoked, and will remove the needle immediately. Those who disregard the patient in excruciating pain risk making a minor injury severe, and a temporary injury permanently disabling. If you are performing within the standard of care, you're removing the needle whenever the patient expresses unusual or extreme pain, tingling or numbness in the fingers or hand, and any electrical, shooting-pain sensation.

3. Stick the first vein you find

First come, first served works well for a soup kitchen, but it doesn't apply to veins that present themselves for venipuncture. The standards urge us to perform a thorough survey of both arms (if available and accessible) for the presence of a vein that is least likely to be near nerves and the brachial artery. That means avoiding the basilic vein and any other vein that lies on the inside (medial) aspect of the antecubital area. If you're not confident either can be successfully accessed, you can attempt to draw from a basilic vein, but not until the safer median and cephalic veins of both antecubital areas have been ruled out.

2. Probe

Nobody likes to admit defeat. But in phlebotomy, failing to surrender to a missed vein can lead to probing around until blood is obtained. Sooner or later, those who do seem to end up injuring patients. Nerves and the brachial artery can be easily injured when the collector probes for a basilic vein missed upon initial insertion. The reasonable and prudent phlebotomist recognizes this risk, however, and removes the needle instead of giving in to temptation to salvage the draw. Make sure you know it's beneath the standard of care to laterally relocate the needle when you miss the basilic vein.

1. Misidentify/mislabel

Do you ask patients to state their full name and birth date as a way to confirm the arm bracelet is correct? Do you require them to spell their first and last names? The standards require it. Patients can suffer serious complications and death when an arm bracelet is all that is relied upon to establish a patient's identity.

Do you rely on arm bracelets that are not attached to the patient? You shouldn't. An identification bracelet that is taped to the bedrail identifies the bedrail; nothing else.

Make sure your procedure manual clearly spells out that all specimens must be labeled at the patient's side after the draw (not before) without exception. If you're a supervisor or manager, be sure to discipline infractions. It's that important.

There are many more than ten ways to harm a patient during venipuncture. But the ten discussed in this series are likely to be the most common. To immunize your specimen collection staff from inflicting an injury during a venipuncture and the legal firestorm that can follow, make sure they know the standards for the procedure, and that your manuals reflect them. When fully galvanized to the standards in policy and practice, your facility could likely find itself on a different kind of list: Top Ten Safest Labs to Draw Your Blood.

Note: for a short, poignant video putting the cost of phlebotomy errors in human terms, view Preanalytical Errors: Real People, Real Suffering.